Science Fell in Love, So I Tried to Prove It is a comedy about two intense postgraduate students who develop feelings for each other in their research lab. Before the first set of opening credits, elegant and confident Himuro states her feelings for her aloof intellectual rival, Yukimura. He is stunned, and expresses cautious interest, but isn’t sure his feelings are love. “What is the definition of ‘love’?” he asks. “Himuro, upon what evidence did you determine that you love me?”

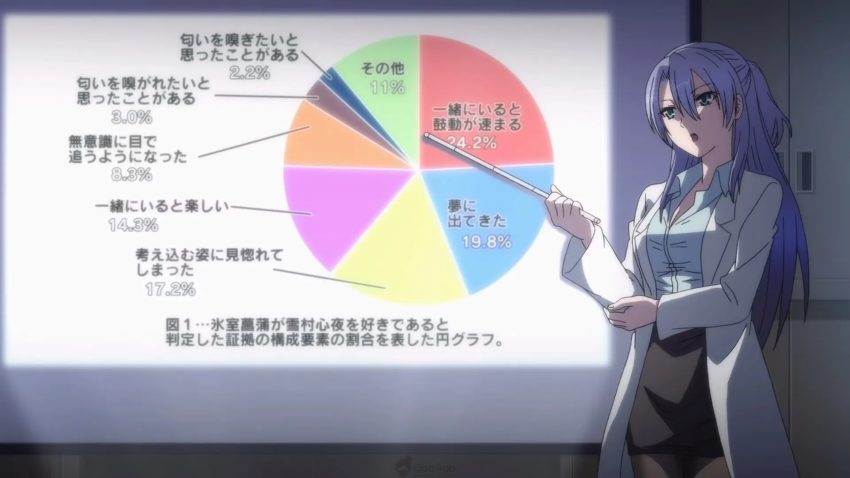

You’d expect Himuro to be upset, but she isn’t. On the contrary, she is delighted by his challenge, and presents a thorough argument, with pie-charts, graphs, and a working hypothesis. In this scene and beyond, the series turns into a fantastic representation and allegory for the experience of online dating. Just not literally.

For a start, it works on the same premise and processes as a dating app. After Himuro’s presentation, she and Yukimura evaluate her argument, adjust the hypothesis, and determine a new research project: to establish the ‘base conditions’ of love, the signs that anyone in love is guaranteed to experience. They intend to use these to construct a Turing machine that can answer the question “Is this love a 0 or a 1?”

In other words, scientists are searching for the right numbers to accurately assess the viability of a romantic relationship before it begins. That’s the premise of Science Fell in Love and every dating app out there from eHarmony to OK Cupid. “Romantic affection, and the question of its determination, can be rendered as a formula.”

Ask a question, and make an educated guess at what the answer could be. Test your guess, learn from the results, repeat. That’s the scientific method in a nutshell, which drives Himuro and Yukimura’s research, and their relationship. Online dating apps don’t use data from wearables like smart watches (yet). But whoever is advocating for it behind the scenes may well sound like Yukimura: “If we monitor heart rate, we can quantitatively measure ‘thrilling palpitations of love’.”

Digital dating entrepreneurs have worked this way for years. Back in 2014, in an OK Cupid blog post titled ‘We Experiment on Humans!’, co-founder Christian Rudder said: “If you use the Internet, you’re the subject of hundreds of experiments at any given time, on every site. That’s how websites work.” And if you want to tell a story about an internet-based industry without actually showing computer scientists at work, computer scientists in a lab are a sensible side-step. Scientists like Himuro and Yukimura are a particularly good choice. Empirical to a fault, their insistence on prizing logic over emotion helps approximate online dating dynamics in their 100% offline relationship.

When complete strangers agree by text-message that they see the potential to sleep together/get married/raise children, it adds a shot of intimacy to their otherwise distant relationship, with nothing in between. Because of this, couples who match online have a different dynamic on their first date than couples who crushed on each other in person, or who show up to a blind date.

Science Fell in Love parallels this dynamic by swapping interpersonal unfamiliarity for extra emotional distance, gag-manga style. One way it does this is by inverting the online dating mentality. Many people come to online dating with a shopping list, intending to take no risks until they find someone who meets a lengthy checklist of conditions. However, Himuro and Yukimura intend to take no risks until they find a lengthy checklist of conditions to justify their existing interest. In both cases, the goal is to keep attraction at arms’ length until the data lines up.

The show also inverts specific online dating experiences. For example, when Himuro states her feelings for Yukimura, both are sitting with their backs to each other, staring at computer screens while they talk. Where app users may play it cool in DMs and freak out in real life, Himuro and Yukimura speak calmly while their typing dissolves into gibberish.

Himuro and Yukimura are naturally detached characters who find a way to turn romantic exploration into their job. Each aspires to “always deal with things calmly and intellectually.” So, their choice to explore their feelings through a lab-wide research project rather than, say, dinner and a movie, actually downgrades their intimacy from comfortable rivals to awkward new colleagues.

While the experiments they run do bring them closer, they frequently interrupt that closeness to record observations, or doom it from the start by prioritising efficiency. They communicate more as collaborating researchers than potential partners, hiding their desires and fears behind clinical analysis and academic theories. All this extra distance largely mitigates the impact of their pre-existing relationship on their romantic prospects. Because of this, their relationship develops more like a couple who met online than a workplace romance.

If Science Fell in Love were about two people who met through an app, you wouldn’t need to change much about their relationship. Consider:

Figure 1: After their efficient and matter-of-fact expression of mutual interest, Himuro and Yukimura arrange meetings where they can act out different relationship behaviours. They analyse their actions and reactions in depth to assess their romantic potential.

Figure 2: Both find it hard to trust their own instincts, instead relying on what the data says. As a result, each new piece of information has a disproportionate influence on their own opinions of their romantic potential.

Figure 3: When a sentiment is difficult to voice, both use text-based communication instead. At one point, they even set up a way to accurately record their emotions towards each other through one tap on their phone screens.

If you’ve ever tried online dating, some of this may sound familiar.

Himuro and Yukimura’s first on-screen interaction is exactly one minute of verbal sparring followed by Himuro telling Yukimura that she has feelings for him. The start of many happily-ever-afters in the internet age. A far cry from the longing glances and dramatic confessions more typical of anime romance.

The two of them rarely refer to their time together before the series, and never in detail. From the audience’s perspective, their relationship begins with the equivalent of twelve messages and an expression of mutual interest that transforms their previous dynamic. It’s one of the most efficient starts to a requited romance in anime, featuring two of the most obvious candidates for online dating.

With some anime couples, you have to wonder how compatible they actually are. Are they happier together than they would be with anyone else, or just childhood sweethearts who believe in fate? What fuels their relationship: is it true love, or the traumatic event they went through together in season one? Not so in Science Fell in Love. Instead, you have to wonder if either of these people could ever make a romantic relationship work with anyone else. Himuro and Yukimura’s language is science. Interrupting a hug to review their respective heart rates might look unromantic, but they enjoy these experiments in their entirety. They are never happier or more attracted to each other than when converting a real-world problem into equations they can solve.

This intense devotion to rigorous analysis puts off other love interests and makes progress slow. But it’s also exactly what draws Himuro and Yukimura together and gives their relationship a fire no-one else understands.

They’re unusual. The way they communicate is unusual, the activities they enjoy most are unusual, and the way they approach romance is unusual. From what we see of their backgrounds, this has always been the case, and has often isolated them from their peers. Niche online dating is perfect for people like this, social outsiders on the same wavelength. Himuro and Yukimura’s relationship shows what online dating can achieve at its best.

And anime is the best medium to portray online dating. One of the biggest challenges for any online dating series is that text-based interactions are boring to watch. Most of us understand now that on-screen ‘hacking’ looks nothing like the real thing. But that convention was set before many people knew what the real thing looked like. Everyone knows what online dating looks like, warts and all, whether they’ve used it or not. At its worst, you’re seeing dick pics and getting ghosted. At its best, you’re chatting happily in DMs. How do you make that look interesting, let alone romantic?

Internet romance is a steamy sub-genre in novels but rarely the central topic of any TV show or film, in Japan or otherwise. Anime has the best shot of making online dating into an aesthetically pleasing story though. The most unimaginative way to show text-based interactions is through close-ups of screens, typing fingers, moving eyes, reading out loud. Anime takes this option often. But on the other end of the spectrum, you have the overlapping speech bubbles in the superflat Summer Wars netscape.

Between those two extremes is a range of less creative but still visually interesting options. The obvious option is to have characters interact in the form of online avatars, but Science Fell in Love takes another tack, illustrating Himuro and Yukimura’s communication with lively equations, graphs, and charts. Just as often, though, it cuts to manga panels, sumo wrestlers, classic anime, fairy tales, dating sims, sports, computer animations, stick figures, and other aesthetics. It’s vibrant and engaging, bringing dry data points to life.

But why is online dating all but absent from anime? The first reason is simple: stigma.

In 2018 YouTuber That Japanese Man Yuta hit the streets of Tokyo to ask young passers-by if they had heard of Tinder. Most hadn’t, though one recalled it being “some sort of app for talking with foreigners.” When asked about other dating apps, most had no experience or interest, assuming the accounts would be fake or that they’d be swindled out of money.

The earliest dating websites in Japan, known as deai-kei (literally ‘encounter’) sites, quickly became notorious for crimes like fraud and solicitation. The result was a stigma around online dating that’s taken two decades, a generation of Facebook use, and a pandemic lockdown to turn the tide.

Luckily for online dating companies, the emergence of the word konkatsu in 2007 opened the door for a rebranding. Konkatsu is a term to describe the active search for a partner to marry. For Japanese singles in 2007, konkatsu mostly referred to activities like asking a friend to introduce them to new people or attending goukon (group dates), both still popular options. But the dating industry spotted an opportunity. Within two years there was a ‘konkatsu boom’ of commercial services to facilitate the search for a spouse. Nowadays, konkatsu services (and renkatsu services, to aid a search for love without the focus on marriage) form a complex ecosystem of matchmaking agencies, live events, and online activities.

Dating apps and websites are not only part of this ecosystem, but legitimised by it. Because konkatsu is seen as one solution to Japan’s dangerously low birth rate, there’s a lot of institutional support for it. That support has become more and more digital, especially since the global pandemic has simultaneously worsened the birth-rate crisis and made it harder to meet new people by chance.

Local officials facilitate machikon, city-wide matchmaking events, now also online. The Japanese government owns around 25 matchmaking agencies, and in 2020 announced funding to subsidise AI upgrades for those agencies. Some companies even pay for dating app memberships as an employee benefit. Being in this category makes online dating more respectable and trustworthy.

Not everyone in Japan does konkatsu, of course. But it’s not a tiny niche, either. Of the people who got married in Japan in 2019, it’s reported that 30% had been using konkatsu services. Many more have used konkatsu services – including online – for fun, friends, and FOMO. Japan’s dating landscape is full of varied relationship types, dating tools, and motivations for finding a partner.

But anime shows almost none of that variation, because romance anime are almost all based in fantasy. Some romance anime are based in the fantasy genre, involving supernatural beings, magical powers, and other worlds are common. Some show more mundane fantasies, like childhood promises, foreign settings, or harem households. Most often though, the fantasy is nostalgia, set in historical periods or – the big one – teenage years. Look up any anime romance listicle, remove anyone young enough to be in high school, and see what’s left.

This is the second reason online dating is so rare in anime: the industry’s bias towards youth. Romances between human adults in anime set in contemporary, real world Japan are rare. Even then, most of those adults are university age, not ready for the konkatsu that makes online dating respectable. Sure, it’s unreasonable to expect any one medium to represent an entire country’s romantic landscape. But it’s striking how little of that landscape anime covers compared to Japanese TV, films, novels, and manga.

In anime, adults most often fall in love through education, house-share, or shared passions. Nothing wrong with that, of course. But there are so many more relationship origin stories that other Japanese media explore and anime doesn’t touch. In 2020 alone, Japanese TV dramas showed adults falling in love through all of the above, plus omiai (a formal matchmaking introduction), quickie marriage, dating apps, government matchmakers, social media, even social distancing at home! They showed romance between old people, queer people, an international couple with children… And 2020 wasn’t special.

Manga and novels offer even more diverse stories, some of which become boundary-pushing series like 38sai Batsuichi Dokushin Onna ga Matching Apuri wo Yattemita Kekka Nikki (The Results Diary of a 38-Year-Old, Divorced, Single Woman Who Tried Dating Apps). While the title makes it sound like a light novel, it’s actually a memoir, based on the true story of a Tokyo resident enjoying her single life with younger men and celebrities. Anime just doesn’t tap into the same range of potential options.

Occasionally a series will add some nuance. In 2017, mid-career professionals met in a digital space in Recovery of an MMO Junkie… but the space was an MMORPG, and didn’t bring them together in real life. In 2020, Rent-a-Girlfriend had undergrad students meeting through an app… but as escort and client, slotting into old deai-kei associations. While serials like this add welcome variety, they are few and far between. There is one outlier going above and beyond to balance the scales, though, and that’s Aggretsuko.

Main character Retsuko, a company accountant in her mid-twenties, develops crushes and enters romantic relationships as you would expect. But she also dabbles in konkatsu, despite not wanting to get married yet, attending an omiai, goukon, and ‘omiai party’ (speed dating for marriage prospects). On top of this, Aggretsuko has so far showcased a female employee quitting work when she got married, a divorcee with no interest in remarriage, a woman in her forties investing in konkatsu, a working mother, and more. It’s refreshing for an anime to give so much attention to adult women navigating dating, love, and marriage.

With one notable exception: online dating. Season three of Aggretsuko does introduce a dating app… as a prototype for a character’s side hustle. No character at any point uses the app with the intention to find a date with it. Aggretsuko features a VR boyfriend who puts you in debt through microtransactions, but doesn’t want to deal with online dating.

And this is the third reason online dating doesn’t show up in anime: because anime doesn’t often represent stigmatised industries literally. Take love hotels. In Japan, their pay-by-the-hour rooms attract three main demographics: sex workers, people having affairs, and keen young couples. In anime (that isn’t hentai, which is a separate genre with its own conventions), they’re mostly a place to shelter (Weathering with You) or to kill time (Beastars). They become sites of safety or comedy, sometimes even sexuality. Sex work? Infidelity? Not so much.

In light of all that, Science Fell in Love, So I Tried to Prove It successfully packages the feel of online dating to make it both more acceptable for Japanese audiences and pleasing to romance fans expecting characters to fall in love organically. It has the same premise as a dating app, and follows the same processes. The characters are highly compatible misfits, the kind online dating excels at bringing together. They interact in a way that brings online dating hallmarks like a quick start, emotional distance, and over-analysis into their relationship. The romance progresses in a similar way to relationships that start online.

As for online dating in the real world, the industry in Japan grew by 23% in 2020, and is predicted to more than double that growth in the next five years. The pandemic has further tanked Japan’s marriage rate and forced more traditional matchmaking services online, where they are thriving. For the first time ever, online dating is about to be big in Japan – and anime is the perfect medium to represent it, because anime creators aren’t chained to the literal.